FALLING ON DEAF EYES Unites Punk Rock and the Deaf Community

A 2019 Hollywood Fringe Festival standout

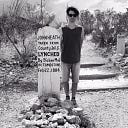

Justin Maurer wears many hats. Touring punk rocker with three different bands, traveling dental equipment salesman, published author, and you may have even caught him on clips from the six o’clock news during the recent L.A. Teacher’s Strike, as the animated and rambunctious ASL (American Sign Language) interpreter for the speeches of union leaders and even Mayor Eric

Garcetti.

Maurer is the kind of modest, blue-collared artist that often gets overshadowed nowadays by influencers (and rich kids feigning outsider art), and he’s putting all his talents under one roof. His multimedia play — Falling on Deaf Eyes — is both personal and informative, telling the story of his deaf mother grappling with the chaos of single motherhood and raising her punk kids in the

rural Northwest. It premieres at the Hollywood Fringe Festival, running from June 9 through June 23 at the McCadden Place Theatre.

In a unique move, Maurer is combining his lifelong passion of live performance with his personal experiences as a CODA (child of a Deaf Adult). He has enlisted a range of local L.A. talent, including director Jevon Whetter, actor Lisa Hermatz (both of whom are deaf educators he met during the Teacher’s Strike), voice actor Jann Goldsby, and soul-stirring singer-songwriter, STACEY, who not only composed an original score but will be performing it live.

Billed as a comedy, Falling on Deaf Eyes has its share of tragedy and vulnerability too, as it aims to “educate and inform the general public about American Sign Language and some of the daily issues facing the deaf and hard of hearing community.”

I met with Justin Maurer at the 4100 Bar on Sunset Blvd. in Silver Lake, where we talked about his personal experiences and his process for this unique upcoming play.

What was it like growing up with a deaf mother? What are some common

misconceptions that you’ve experienced?

American Sign Language was my first language. I could sign before I could talk. As the eldest child in my family, it was my job to interpret for my mom. Most of the time, I was proud to have the responsibility. Other times, I would have rather been playing with other kids instead of interpreting when she wanted to chat with my friend’s parents at his birthday party, or in church, or later on interpreting for her when she wanted to talk with her crushes. I interpreted for all kinds of situations where a kid probably shouldn’t be, like for the police, bill collectors, and for my mom’s lawyer during my parent’s divorce.

Common misconceptions were that people assumed my mom couldn’t drive. Certain friends’ parents wouldn’t let their kids ride in a car with my mom because she wouldn’t be able to hear police sirens. Other parents mentioned that my mom wouldn’t be able to hear smoke alarms so it was dangerous for their kids to even come over to my house. Other people would ask if my mom could talk, assuming that being deaf means that you have no vocal chords and can’t make any sounds. Think of the old terms “deaf-mute” or “deaf and dumb.” Many people associated deafness with mental disability. People’s ignorance always amazed me, but my siblings and I were usually patient and tried to educate people. My mom is a saint for not being furious at these misconceptions. By adulthood, she was used to it.

Our mom was ostracized her whole life for being different, I think she wanted to fit in, and having kids with green hair and mohawks didn’t exactly help her fit in.

Though you’ve been part of the deaf community all your life, was there anything new you learned during your time working the L.A. Teacher’s Strike?

There was about 100 or so Deaf educators on strike. It was especially personal for me because my deaf mom was a public high school teacher when I was growing up. As far as learning something new, it was being inspired by what a difference people can make when they band together, organize and march. The LA teacher’s strike was emotional, tiring, inspiring. It felt good to wake up every day at 5am and walk into the madness, the organized chaos, the beautiful thing that was 32,000 teachers on picket lines and taking over the entire city of Los Angeles for one week in the rain.

What do you hope people will take away from this performance?

I hope people will have fun. I hope that they will be inspired, and that they will have an interest in learning American Sign Language. I hope that they will acknowledge the Deaf and Hard of Hearing and their subcultures, but most of all I hope that they will respect my mom and everything that she went through.

This story about your family originally started as an idea for a book. Why the dramatic shift from the personal page to the public stage?

As an American Sign Language interpreter in my everyday life, I realized that a lot of my musical and literary events weren’t accessible for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. I wanted to make an event that could bring in fans of punk rock, fans of literature, theatre, and include the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community so that everyone could enjoy a performance. Punk Rock has a

limited audience. Alt-lit has a limited audience. I wanted to get to people, to get to the beating human heart. I wanted to make something happen.

You’re a lifelong punk. How did punk rock shape your formative years?

Punk was like a religion to me when I was a kid. The Do-It-Yourself mentality was so far away from rock stardom, it was taking life by the balls and just going. It was a way out of my small town. It was a way to see the world. I’m very lucky to have been exposed to it at a young age.

Was your mom supportive?

She allowed us to have band practice in our garage or in our basement. I think she worried about what people would think. She was ostracized her whole life for being different, I think she wanted to fit in, and having kids with green hair and mohawks didn’t exactly help her fit in. My sister and I didn’t want to fit in, we wanted to be ourselves. We were angry. We were damaged.

So punk was perfect for us. My mom had trouble understanding why we looked or acted a certain way, and she was certainly concerned about what people thought of us. On the other hand, she let us throw concerts in our basement, she let us have friends over, she liked feeling the drums and bass from the loud music. So she was pretty cool as a mom.

Deaf punk.

Exactly! She was open-minded. She just didn’t like how we looked. She wished that we dressed out of an Abercrombie and Fitch catalog. But we had each other. And that was important, to stick together as a broken family. I had my dad thrown in jail when I was 16 years old when he assaulted my sister. We got a restraining order against him. At that point we had to stick together. We became closer. Part of this play is about that.

What are the elements that make up this production? What can people expect?

There’s sign language, punk rock, storytelling, and theatrical visuals. The play is set on Bainbridge Island, Washington in the 1990s. The rest is a surprise.